|

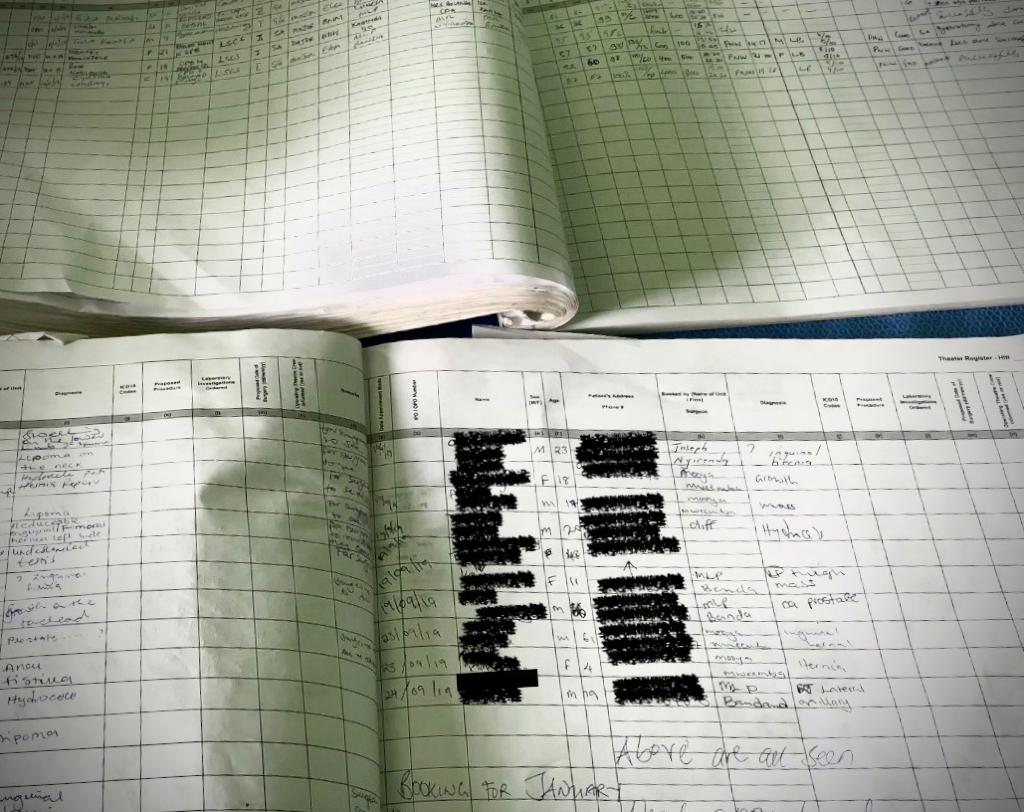

I remember when I told my father my new job would be as a Research Assistant for an EU commissioned project at RCSI, his pride was palpable just from the expression on his face. As an aspiring researcher who just graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Psychology, I too saw this new job as a valuable first step, the opportunity you are always told about. So, I decided on a plan of action: I would follow a strict methodology, one that would yield the most objective results and therefore the best scientific data. On my first day, I began digitising surgical records from Malawian district hospitals, meticulously typing doctors’ written notes into a spreadsheet. Pretty quickly I was faced with the reality of my job: doctors’ handwriting was often less than legible, many diagnoses and procedures were new to me, and entering data column by column was definitely more efficient than row by row. This meant for every page I digitised the date of the surgery was entered first, then the patients’ age, sex, diagnosis, surgical procedure, anaesthesia used, principal surgeon and finally patient outcome. Every page, every hospital, every hour of every day. Soon I developed a method and fell into a groove, a sort of autopilot mode, my eyes like windscreen wipers scanning up and down, my fingers copying and pasting what my eyes saw. I’m not going to lie though: It took its toll. Maintaining focus hour-after-hour required regular trips for coffee refills and natural light during my lunch breaks to ease the eyestrain. Although I was getting better at deciphering diagnoses, learning about obstetric procedures and the complexities of childbirth, I was still largely blind to the greater context of the project. I was pretty content to just stay on-task, follow the method I had developed and hustle through the fatigue. About a month in, I found myself loosening to my surroundings and my imposter syndrome began to wear-off. I got to know the team I was working with, their backgrounds and roles within the project. I saw a compilation of video footage from Mangochi Hospital in Malawi following the experiences of surgeons, nurses, and the goals of SURG-Africa. I learned about the intervention hospitals, the control hospitals, the locations of these hospitals, the capacities of their operating theatres and how they contrasted with my pre-conceived ideas. Although the work I was doing hadn’t changed, my morale was boosted, “How wonderful it is to be part of a project so innovative and benevolent”, I thought. Feeling a greater connection to the team, the project, and my role within it made the next 3 months less grating for sure. After 4 months, 20,000 cases entered and gallons of coffee, I was finished with Malawian and Tanzanian district hospitals moving on to paediatric referral data from QECH in Malawi. This data was different, there were no columns, there were no headings, it was simply lined A4 pages with patient information on each line. My eyes were so accustomed to scanning vertically, column by column, that this was almost a different job to me. Now, I was reading each case. “Night duty 22/1/2017 - 6 F ugib nkhotakota”, for example. With a little bit of investigation, this child’s journey starts to unfold and with it, my imagination ignited:

“She, a 6-year-old child, was referred from Nkhotakota District Hospital travelling some 400 kilometres in the middle of the rainy season to QECH, arriving on Sunday night with signs of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.” Henceforth, my perception shifted. I was no longer concerned about constraining heterogeneity within diagnoses or surgeries. My responsibility was not to the diagnosis, the hospital or even to SURG-Africa, it was to each individual, each child’s journey to QECH’s hospital doors. I realised how different I thought my job was now compared to when I first started. I began with personal motivations, to better myself and my career with a rigorous scientific approach. That was until I learned more about the project, the team, and the hospitals. In hindsight, I was fixated on the data itself, the nuts and bolts, without recognising that without the people there is no data. By shifting from columns to rows I realised the work I was not merely indexing data, but instead reformatting the experiences and stories held by people. The outcome of my work did not change, but how I related to my role did. A revelation that made my final month with RCSI less strenuous and more rewarding. Seán Keary was part of the SURG-Africa team working as a Research Assistant for five months. His important role processing data from Malawian and Tanzanian hospitals has contributed enormously to the project. Seán's story is the perfect illustration of how these, often invisible, contributions are essential to reach the final conclusions of this project.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed